Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Sign up Today for the Continental Army

See if this video makes you ready to sign up! If only George Washington had video technology to turn to for recruitment.

Who was Amerigo Vespucci?

Those who wonder how America got its name inevitably run into Amerigo Vespucci. Who was he? And why are we named after him - and not Christopher Columbus, who got here well before Vespucci did?

To read up on Mr. Vespucci, follow this link to a great article by Roger Saunders, the Feature Writer-Editor for American History over at Suite101.com.

Want something a little different? Check out this homemade school project video on Vespucci by clicking here. It's not exactly fully accurate, but...it's kind of neat.

For a biographical essay on Vespucci, click here.

You can also check out what Wikipedia has to say about Mr. Vespucci by clicking here.

To read up on Mr. Vespucci, follow this link to a great article by Roger Saunders, the Feature Writer-Editor for American History over at Suite101.com.

Want something a little different? Check out this homemade school project video on Vespucci by clicking here. It's not exactly fully accurate, but...it's kind of neat.

For a biographical essay on Vespucci, click here.

You can also check out what Wikipedia has to say about Mr. Vespucci by clicking here.

Saturday, July 19, 2008

"America the Beautiful" on "America's Mountain"

O beautiful, for spacious skies,These eloquent and patriotic words to the now infamous song, America The Beautiful have captivated the heart and soul of an entire nation. Written in 1893 by English professor Katharine Lee Bates, the song has actually been considered on numerous occasions to be a replacement to our current national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner. But do you know the origins of this timeless American anthem?

For amber waves of grain,

For purple mountain majesties

Above the fruited plain!

O beautiful, for pilgrim feet

Whose stern, impassioned stress

A thoroughfare for freedom beat

Across the wilderness!

O beautiful, for heroes proved

In liberating strife,

Who more than self their country loved

And mercy more than life!

O beautiful, for patriot dream

That sees beyond the years,

Thine alabaster cities gleam

Undimmed by human tears!

America! America! God shed His grace on thee,

And crown thy good with brotherhood, from sea to shining sea!

As mentioned before, Katharine Lee Bates was an English professor at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. In 1893, Bates accepted an offer to teach a summer semester at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, Co. During her trip, Bates was deeply impressed by the vastness of the American landscape. Upon her arrival to Colorado Springs, Bates could not help but notice the majestic mountain off to the west, known to everyone as "America's Mountain," or Pikes Peak as we know it today.

As mentioned before, Katharine Lee Bates was an English professor at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. In 1893, Bates accepted an offer to teach a summer semester at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, Co. During her trip, Bates was deeply impressed by the vastness of the American landscape. Upon her arrival to Colorado Springs, Bates could not help but notice the majestic mountain off to the west, known to everyone as "America's Mountain," or Pikes Peak as we know it today.Needless to say, Bates took a train ride to the summit of Pikes Peak in June of 1893. While taking in the breathtaking scenery at 14,110 feet, the words to her legendary poem started to fill her head. The "purple mountain majesties

above the fruited plain" were enough to cause Bates to publish her poem, which was quickly incorporated to the music of Samuel A. Ward to give us America The Beautiful.

In addition to being the inspiration behind America The Beautiful, Pikes Peak has enjoyed a rich tradition of American history that virtually dates back to our nation's beginning. With this in mind, here is some additional history of America's Mountain...Pikes Peak:

1803: The Pikes Peak area is obtained by the United States as part of President Thomas Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase. Colorado was on the fringe of the Louisiana Purchase, so very few Americans knew what the topography of the land.

1806: President Jefferson dispatches Lt. Zebulon Montgomery Pike to determine the southwestern borers of the Louisiana Purchase. In the course of his trek, Pike decides to climb the peak on November 24th, but is unable to reach the summit due to the harsh Colorado winter climate. Pike gives the mountain its first "official" name as Grand Peak. Zebulon Pike was the son of Army Officer Zebulon Pike, Sr., who served under George Washington during the American Revolution. After exploring the Pikes Peak region, Lt. Pike enjoyed a few more years of successfully exploring the western regions of the infant United States. Pike also served with distinction in the Battle of Tippecanoe and eventually served as a quartermaster in New Orleans during the War of 1812. As a result of his honorable service, Pike was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in 1813, and was assigned to lead several outposts along the shores of Lake Ontario. Sadly, Pike was killed by falling rocks and debris during a confrontation with the British.

1806: President Jefferson dispatches Lt. Zebulon Montgomery Pike to determine the southwestern borers of the Louisiana Purchase. In the course of his trek, Pike decides to climb the peak on November 24th, but is unable to reach the summit due to the harsh Colorado winter climate. Pike gives the mountain its first "official" name as Grand Peak. Zebulon Pike was the son of Army Officer Zebulon Pike, Sr., who served under George Washington during the American Revolution. After exploring the Pikes Peak region, Lt. Pike enjoyed a few more years of successfully exploring the western regions of the infant United States. Pike also served with distinction in the Battle of Tippecanoe and eventually served as a quartermaster in New Orleans during the War of 1812. As a result of his honorable service, Pike was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in 1813, and was assigned to lead several outposts along the shores of Lake Ontario. Sadly, Pike was killed by falling rocks and debris during a confrontation with the British.1820: Dr. Edwin James, a historian and naturalist, becomes the first recorded person to reach the summit of Pikes Peak. He decides to rename the mountain James Peak for obvious reasons.

1840: The official name of Pikes Peak is adopted by Major John Charles Fremont in honor of Lt. Zebulon Pike.

1858: Julia Archibald Holmes becomes the first woman to climb Pikes Peak.

1860: Construction of the Ute Pass wagon road begins. The current road up Pikes Peak still follows most of this original wagon road.

1886-1888: The construction of the carriage road/train is built.

1893: Katharine Lee Bates writes, America The Beautiful, most of which she composed while on the summit.

1916: The first ever Pikes Peak Hill Climb is held. This is the second oldest automobile race in the United States, behind the Indianapolis 500.

What I find so interesting about the history of Pikes Peak is that it literally ties the history of the eastern United States -- where almost all of our nation's heritage and founding took place -- with its western future. America's Mountain as it is appropriately named symbolically joins the nation together as one. The east's rich history of American enlightenment and founding is able to link up with the west's rugged beauty and prosperous future thanks in part to this majestic 14,000 foot peak. No wonder Katharine Bates concluded her epic song with the words, "From sea to shining sea."

What I find so interesting about the history of Pikes Peak is that it literally ties the history of the eastern United States -- where almost all of our nation's heritage and founding took place -- with its western future. America's Mountain as it is appropriately named symbolically joins the nation together as one. The east's rich history of American enlightenment and founding is able to link up with the west's rugged beauty and prosperous future thanks in part to this majestic 14,000 foot peak. No wonder Katharine Bates concluded her epic song with the words, "From sea to shining sea."Here are a few pictures from my family's visit to America's Mountain, Pikes Peak:

During the Colorado gold rush of the 1800s, travelers heading west used to regularly adorn the sides of their wagons with, "Pikes Peak or Bust." Cripple Creek, which is located close to Pikes Peak, was the location of Colorado's second largest gold mine, so naturally travelers from the east would scan the horizon looking for their first glimpse of Pikes Peak.

At the base of America's Mountain, which is about 8,000 feet. Only 6,000 more to go!

On our way up the mountain we noticed that we were indeed, "Above the fruited plains."

Half way up the mountain, and the road is beginning to look like the old wagon rout of the 1800s!!!

Yep, we are officially above timber line.

Looks like a highway to heaven!

And now we are walking in the clouds...literally!

We made it! 14,000 feet never felt so good...or so hard on the lungs!

A view of Colorado Springs and the frontier to the Great Plains from more than two miles high.

Here is my family (out of breath and all) at 14,110 feet.

Oh yeah, be careful while coming DOWN the mountain!

For your enjoyment here is the most popular rendition of America The Beautiful by none other than Ray Charles:

Labels:

Katharine Lee Bates,

Louisiana Purchase,

Memorials,

Music,

Videos

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

"America is a Christian Nation...But so is Hell": Garry Wills on Separation of Church & State

Pulitzer Prize winning author and historian Garry Wills discusses separation of church and state. Excellent video.

Friday, July 11, 2008

Gary Nash on "Conservative-Culture Warriors" and Historical "Revision"

Historian Gary Nash of UCLA is not only one of the most respected historians on early American history, but has also received praise for the fact that his scholarship has breathed new life into America's sense of historical appreciation. In recent years, Nash's work has challenged many of the traditional assumptions surrounding America' founding. Everything from the role of slavery and women to the influence of religion on America's 18th century revolution has been a part of Nash's "assault" on traditional early American historiography.

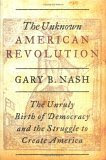

Historian Gary Nash of UCLA is not only one of the most respected historians on early American history, but has also received praise for the fact that his scholarship has breathed new life into America's sense of historical appreciation. In recent years, Nash's work has challenged many of the traditional assumptions surrounding America' founding. Everything from the role of slavery and women to the influence of religion on America's 18th century revolution has been a part of Nash's "assault" on traditional early American historiography. In his most recent book, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America, Nash challenges the idea that the American Revolution was merely a conflict between rival elites in Britain and America. Instead, Nash boldly proclaims the revolution as being inspired and led by the masses.

In addition, Nash challenges a number of the beliefs held by Christian Nationalists in regards to America's founding. Nash proclaims America's establishment and success as being the result of enlightened secularist ideology, which caused the American populace to challenge the social, political and religious norms of their day. In so doing, America became not a "Christian" government but a secular institution, which sought to keep religion and government separate from one another.

Naturally, the scholarship of Gary Nash does not sit well with hard-core Christian apologists such as David Barton and others. In response, Christian zealots have sought to label historians like Nash as being "unpatriotic" or as "secular revisionists" that are bent on eliminating any and all remnants of America's "Christian heritage."

Gary Nash was not ignorant of the fact that his work would stir up hostilities. In his introduction, Nash addresses his critics by writing the following:

When historians fix their gaze downward or write a warts-and-all American history, they often offend people who cherish what they remember as a more coherent, worshipful, and supposedly annealing rendition of the past. In the history of the 1990s, many conservative-culture warriors called historians offering new interpretations of the American Revolution – or any other part of American history – “history bandits,” “history pirates,” or, sneeringly, “revisionists” intent on kidnapping history with no respect for a dignified rendition of the past. Yet the explosion of historical knowledge has invigorated history and increased its popularity...Then Nash puts the smack down on those who favor a "traditional" interpretation of the American Revolution as being exclusively a conflict of the elite:

Unsurprisingly, those of the old school do not like to hear the question "whose history?" It is unsettling for them to see the intellectual property of the American Revolution, once firmly in the hands of a smaller and more homogeneous historians' guild, taken out of their safe boxes, put on the table, and redivided. Yet what could be more democratic than to reopen questions about the Revolution's sources, conduct, and results? And what is the lasting value of a "coherent" history if the coherence is obtained by eliminating the jagged edges, where much of the vitality of the people is to be found? How can we expect people to think of the American Revolution as their own when they can see no trace of their forbears in it?

A history of inclusion has another claim to make. Only a history that gives play to all the constituent parts of society can overcome the defeatist notion that the past was inevitably determined...Honest history can impart a sense of how the lone individual counts, how the possibilities of choice are infinite, how human capacity for both good and evil is ever present, and how dreams of a better society are in the hands of the dispossessed as much as in the possession of the putative brokers of our society's future.If this is "secular revisionism," or "historical piracy" then count me in!

Thursday, July 10, 2008

Native Americans and the Lost Tribes of Israel

The indigenous tribes of the "New World" have been a source of fascination not only for modern scholars, but for early American colonists as well. For hundreds of years, historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, and clergymen have argued over the origins of the diverse Native American tribes that once encompassed the entire face of North and South America. Even in our modern society, scholars of all types continue to argue over the origins of the indigenous tribes of the Americas, despite advances in genetics, cultural anthropology and history.

The indigenous tribes of the "New World" have been a source of fascination not only for modern scholars, but for early American colonists as well. For hundreds of years, historians, anthropologists, archaeologists, and clergymen have argued over the origins of the diverse Native American tribes that once encompassed the entire face of North and South America. Even in our modern society, scholars of all types continue to argue over the origins of the indigenous tribes of the Americas, despite advances in genetics, cultural anthropology and history.Perhaps the most provocative of all the theories regarding the origins of Native American tribes is the belief that they could be somehow linked to the 10 lost tribes of Israel. Even the earliest settlers and explorers of the New World were intrigued by the possibility of encountering a lost remnant of the House of Israel in the New World. Christopher Columbus, the man credited with "discovering" the New World, proclaimed that these newly discovered "Indians" were, in fact, of Jewish origins. Columbus even suggested that Spain could, "recruit their bodies and their wealth to assist Europeans in a final crusade to crush Islam and reclaim Jerusalem" (Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settlement of North America, 33).

After the American Revolution, the fascination with Native American origins was carried to new heights. Despite the fact that no obvious proof could be found to substantiate the claim that Native Americans were the lost tribes of Israel, scores of religious zealots hoped to uncover this claim's validity. Just before embarking on their continental trek, President Thomas Jefferson wrote a brief letter to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark in which he instructed them to "acuire what knolege you can of the state of morality, religion & information among them [the Indians] as it may better enable those who endeavor to civilize & instruct them." In addition, Jefferson shared a personal correspondence with his friend, Meriwether Lewis, in which he expressed his hope that the trek west might provide evidence as to the whereabouts of the lost tribes of Israel (Stephen Ambrose, Undaunted Courage, 154).

In addition to the president, Dr. Benjamin Rush revealed his hope for the discovery of the lost tribes of Israel when he wrote the following inquiries to Lewis and Clark:

At what time do they rise? What about baths? Murder? Suicide? Are any animal sacrifices in their religion? What affinity between their religious Ceremonies & those of the Jews? [my emphasis].Though the Lewis and Clark expedition never returned with any evidence to support the Native American/lost tribes of Israel claim, the legend remained extremely popular throughout the early part of the 19th century. Ethan Smith, for example, who was not only a pastor to a small church in Vermont but was also a self-proclaimed expert on Jewish history, hoped to prove the Jewish roots of Native Americans by appealing to the Bible. In his 1825 book, View of the Hebrews, Smith endeavors to point out what he saw as similarities between Native American religious custom and that of ancient Judaism. As Smith states:

In all their rites which I have learned of them, there is certainly a most striking similitude to the Mosaic rituals. Their feasts of first fruits; feasts of in gathering; day of atonement; peace offerings; sacrifices. They build an altar of stone before a tent covered with blankets; within the tent they burn tobacco for incense, with fire taken from the altar of burnt offering. All who have seen a dead human body are considered unclean eight days; which time they are excluded from the congregation.For Smith, this was ample proof of God's biblical prophesy that, "he [God] shall set up an ensign for the nations, and shall assemble the outcasts of Israel, and gather together the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth" was being fulfilled (Isaiah 11:12).

In the record of Imanual Howitt, who had traveled extensively throughout the United States in the early part of the 19th century, the Native Americans held a certain intrigue that permeates his writings. Howitt, though not a deeply religious man, had adopted the earlier opinion of William Penn, who believed that the "Indians...developed from the lost tribes of Israel." As a result, Howitt became a passionate advocate for the further study of Indian rituals and customs.

The fervor over the possibility of American Indians being of Jewish descent was only furthered when Barbara Simon published her book, The Ten Tribes of Israel Historically Identified with the Aborigines of the Western Hemisphere in 1836. Aside from quoting a plethora of biblical sources to defend her thesis, Simon also claims that early Mexican paintings found by Spanish conquistadors contain "allusions to the restoration of the dispersed tribes of Israel."

The fervor over the possibility of American Indians being of Jewish descent was only furthered when Barbara Simon published her book, The Ten Tribes of Israel Historically Identified with the Aborigines of the Western Hemisphere in 1836. Aside from quoting a plethora of biblical sources to defend her thesis, Simon also claims that early Mexican paintings found by Spanish conquistadors contain "allusions to the restoration of the dispersed tribes of Israel."In addition to Simon's work, other books emerged during the early part of the 19th century in support of the Native American/lost tribes of Israel theory. Books like A View of the American Indians by Israel Worsley in 1828, American Antiquities and Discoveries in the West by Josiah Priest in 1835, and the before mentioned View of the Hebrews by Ethan Smith in 1825. All of these works combined to create a spirit of enthusiasm that deeply favored the Native American/lost tribes of Israel connection.

Perhaps the most popular -- and most controversial -- interpretation on the origins of Native Americans comes from Mormon founder and prophet Joseph Smith. During his youth, Smith claimed to have received a revelation from a heavenly messenger, who related to Smith the location of a hidden record of an ancient people:

He said there was a book deposited, written upon gold plates, giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent, and the source from whence they sprang. He also said that the fullness of the everlasting Gospel was contained in it, as delivered by the Savior to the ancient inhabitants.This record, which eventually became known to the world as The Book of Mormon was allegedly a scriptural account of God's dealings with a remnant of Jewish descendants who had migrated to America during ancient times. As the Book of Mormon's introduction puts it:

The Book of Mormon is a volume of holy scripture comparable to the Bible. It is a record of God’s dealings with the ancient inhabitants of the Americas and contains, as does the Bible, the fullness of the everlasting gospel.Regardless of their origins, the role of religion in shaping the perception of early American society was extraordinary. The aura of mystery that shrouded the origins of the various Native American tribes kept early Americans in suspense for centuries. For a people who were primarily defined by Christian doctrine, the "Indians" of the New World became a living exhibit of their biblical doctrine. By clothing these native tribes in the robes of the lost tribes of Israel, Christian zealots found an additional motive for their further conversion to their brand of Christianity.

The book was written by many ancient prophets by the spirit of prophecy and revelation. Their words, written on gold plates, were quoted and abridged by a prophet-historian named Mormon. The record gives an account of two great civilizations. One came from Jerusalem in 600 B.C., and afterward separated into two nations, known as the Nephites and the Lamanites. The other came much earlier when the Lord confounded the tongues at the Tower of Babel. This group is known as the Jaredites. After thousands of years, all were destroyed except the Lamanites, and they are the principal ancestors of the American Indians.

Friday, July 4, 2008

Thursday, July 3, 2008

In Preparation for Independence Day

Tomorrow will mark the 232nd birthday of the United States. In a little over two centuries the United States has witnessed some dramatic changes, both for the good and the bad. Despite all of these changes, however, one cannot help but appreciate the wonderful heritage, freedom and prosperity that has helped to sustain America throughout the past 232 years.

Tomorrow will mark the 232nd birthday of the United States. In a little over two centuries the United States has witnessed some dramatic changes, both for the good and the bad. Despite all of these changes, however, one cannot help but appreciate the wonderful heritage, freedom and prosperity that has helped to sustain America throughout the past 232 years.Sadly, a large number of Americans have forgotten -- or never bothered to learn in the first place -- our nation's history. A recent study by NPR News sadly states that most Americans remain woefully ignorant of this nation's heritage. In fact, roughly 40% of all Americans have NEVER ONCE read the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, or any of the other important founding documents of our nation's birth.

I for one find it amazing that Americans are so quick to profess their love, admiration and patriotism for this nation, yet remain ignorant of its history and development. In many ways, this phenomenon is similar to the professing Christian that knows little or nothing about his/her religion's doctrine. How can one profess loyalty or patriotism to a nation or cause if he/she knows nothing of its history? As Cicero stated so many years ago, "History is the witness that testifies to the passing of time; it illumines reality, vitalizes memory, provides guidance in daily life and brings us tidings of antiquity...one cannot become a true citizen without first gaining an understanding of history."

As the barbecue pits begin to heat up and the fireworks are pulled out from the closet, remember that tomorrow's celebration is, in the end, a celebration of America's great heritage. If you are one of those 40% that have never read the Dec. of Independence, the Constitution, etc., then I invite you to correct that mistake, and what better day than tomorrow to do it!

With this in mind, here is a wonderful video on the Declaration of Independence, in which the document is read in its entirety. Also, here are a few links to some historical documents that EVERY AMERICAN should read.

Happy Independence Day!

Here is the EXCELLENT Declaration of Independence Video:

And some other links:

*The Constitution of the United States click here

*Bill of Rights click here

*Articles of Confederation click here

*Patrick Henry's "Give Me Liberty of Give me Death" speech click here

*James Madison's "Memorial and Remonstrance" click here

*Thomas Jefferson's "Notes on the State of Virginia" click here

Catholic/Protestant Wars in the Old and New Worlds

The traditional view of early colonial historiography has divided the various wars between England and France -- in both the New and Old Worlds -- into separate conflicts that are seemingly unrelated to one another. Instead of seeing these various wars as being linked with one another, many historians have chosen to classify these various Franco-English wars as unique and individual conflicts. For example, from the latter part of the 17th century to the middle of the 18th, historians have traditionally taken note of four SEPARATE conflicts between the French and the English: King William's War, Queen Anne's War, King George's War and the French and Indian War -- as they were known in the colonies. However, what is often an overlooked fact of these conflicts is the reality that they all shared the same underlying root cause: religious intolerance.

Here is a list of the major Franco-English conflicts during the late 17th and 18th centuries:

Date: In Europe: In America:

1688-1697

In Europe: War of the League of Augsburg

In America: King William's War

1701-1713

In Europe: War of Spanish Succession

In America: Queen Anne's War

1740-1748

In Europe: War of Austrian Succession

In America: King George's War

1756-1763

In Europe: Seven Years' War

In America: The French and Indian War

***Chart taken from A Religious History of the American People by Sydney Ahlstrom, 58.***

From this chart, it is evident that a repeating cycle of violence and intolerance between England and France -- in both the New and Old Worlds -- was keeping these two rival nations in a constant state of war with one another. But what was main cause for such violence? What main factor continued to bring these two neighbors into conflict with one another?

Regardless of the smaller instigating factors of each of these wars, there remained a steady stream of religious fervor, which proved to be the main catalyst for war in each occasion. As colonial historian Karen Kupperman points out:

On the French side, religious passions were every bit as hot as their English foes. Sydney Ahlstrom has pointed out in his book A Religious History of the American People:

By choosing to look at these various conflicts through the lens of religious enthusiasm, we can clearly see that these wars were not separate quarrels but were, in fact, linked through a chain of religious intolerance. English Protestants, still burning with the fires of the Reformation, saw the New World as an additional arena where Catholic supremacy threatened to destroy God's TRUE work. French Catholics, inspired by the resurgence of Catholic piety, sought to spread the Pope's dominion across the seas and choke out the rebellion of the Protestant heretics.

Here is a list of the major Franco-English conflicts during the late 17th and 18th centuries:

Date: In Europe: In America:

1688-1697

In Europe: War of the League of Augsburg

In America: King William's War

1701-1713

In Europe: War of Spanish Succession

In America: Queen Anne's War

1740-1748

In Europe: War of Austrian Succession

In America: King George's War

1756-1763

In Europe: Seven Years' War

In America: The French and Indian War

***Chart taken from A Religious History of the American People by Sydney Ahlstrom, 58.***

From this chart, it is evident that a repeating cycle of violence and intolerance between England and France -- in both the New and Old Worlds -- was keeping these two rival nations in a constant state of war with one another. But what was main cause for such violence? What main factor continued to bring these two neighbors into conflict with one another?

Regardless of the smaller instigating factors of each of these wars, there remained a steady stream of religious fervor, which proved to be the main catalyst for war in each occasion. As colonial historian Karen Kupperman points out:

We should not underestimate the emotional force of this confrontation between Christians, which has been compared to the Cold War of the twentieth century. Each side believed the other was absolved by its religion of all normal moral and ethical behavior in dealing with the enemy, and capable of the most heinous plots.(From Roanoke: The Abandoned Colony, 4)For the English, there was nothing worse than facing the possibility of a New World being ruled by the Pope.

On the French side, religious passions were every bit as hot as their English foes. Sydney Ahlstrom has pointed out in his book A Religious History of the American People:

"During the century in which France's colonial aspirations awakened, there also occurred a remarkable resurgence of Catholic piety...In New France the faith and institutions of the Roman church gained a centrality and importance that was equaled in no other empire, not even New Spain." (59-61).Faced with such religious enthusiasm on the part of the English and the French, it comes as no surprise that this "holy war" would go unresolved for almost a century.

By choosing to look at these various conflicts through the lens of religious enthusiasm, we can clearly see that these wars were not separate quarrels but were, in fact, linked through a chain of religious intolerance. English Protestants, still burning with the fires of the Reformation, saw the New World as an additional arena where Catholic supremacy threatened to destroy God's TRUE work. French Catholics, inspired by the resurgence of Catholic piety, sought to spread the Pope's dominion across the seas and choke out the rebellion of the Protestant heretics.

Labels:

France,

Great Britain,

Religion,

Seven Years' War

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)